This article summarises research undertaken by Lucy Hayes, Stephen O’Neill, Max Spohn (during his time working for the FCA) and Cherryl Ng.

You may be familiar with the jumping green owl celebrating your completion of a Duolingo language lesson. Or perhaps you compete against your friends on Strava to run the most miles in a month. These are all examples of gamification – the use of game design elements to make tasks more engaging and attractive.

With an unprecedented shift towards digitalisation in financial services during the Covid-19 pandemic, policymakers are increasingly concerned that online businesses can manipulate consumers in new ways and more easily than ever before. The FCA’s new consumer duty calls out harmful ‘sludge’ design practices – excessive frictions that prevent consumers making decisions in their own interest. And its 2022/3 business plan sets out its commitment to ‘shaping digital markets to achieve good outcomes’.

Gamification may seem like an innocuous cousin of sludge, but our research into its use in trading apps suggests it can sometimes play a role in driving poor outcomes for consumers.

The rise in popularity of trading apps

Trading apps allow retail investors to trade directly and easily in a range of products, including fractional shares and high-risk investments such as crypto assets and contracts for difference (CFDs). 1.15m new accounts were opened by 4 trading app firms in the first 4 months of 2021, almost double the amount opened with all other retail investment services combined. Many of these customers were new to investing and younger than traditional investors.

We evaluated firms’ use of digital design features as part of a wider FCA assessment of these apps. This evaluation work supports the aim of our Consumer Investment Strategy for a consumer investment market where consumers can invest with confidence, understanding the risks they are taking and the regulatory protections provided.

It also supports the cross-cutting commitments set out in our three year strategy published this year, including putting consumers’ needs first and shaping digital markets to achieve good outcomes.

Evaluation of design features which may be linked to consumer harm

We selected several firms to demonstrate their apps to us, and it was clear that an extensive behavioural design toolbox had been used to create them. Many of the features used give us cause for concern, based on the existing behavioural theory and literature. We give some examples here.

We found gamification techniques that use positive reinforcement immediately after a trade, such as celebratory messages and falling confetti (Figure 1). We also found the use of points, badges and rewards for undertaking certain behaviours and ‘leader boards’ that rank people based on these rewards (Figure 2). We are concerned that these positive reinforcements may encourage people to trade more frequently or make investment choices that they otherwise wouldn’t. For example, A recent study found that celebratory messages and badges can lead people to take on more risk when investing.

We found frequent push notifications with the latest market news on stock movements (Figure 3) and lists that draw attention to real-time price changes by flashing red and green, as well as lists of stocks that had seen the largest price movements in the last 24 hours. We are concerned that giving information to consumers in this way may lead them to pay attention to spurious information and make investments which are not in their interests. Research has found that push notifications can stimulate people to trade in a riskier way using higher leverage and trading larger amounts, with the biggest impact on younger and less experienced investors. Displaying ‘leader boards’ for stocks that have seen the largest price changes in the last 24 hours have been shown to drive consumers to pay attention to and trade on the basis of this information, making poorer returns as a result.

Other features are likely to influence consumer choice such as how much to invest. For example, we found that investment amounts and the amount of leverage offered were sometimes defaulted to high amounts (Figure 4). There is extensive literature showing that people are much more likely to stick to a default.

Example figures

Figure 1: Example of falling confetti celebrating a stock trade

Figure 2: Example of the use of trader leaderboards

Figure 3: Example of frequent push notifications with market news

Figure 4: Default amounts for investing and leveraging

We are also concerned that the app features may blur the lines between online investing and gambling-like behaviours as suggested by another study. Previous FCA research has shown that for many younger, new investors, emotions such as thrill and excitement are key drivers for investing. This might be especially heightened for investing in riskier investments such as cryptoassets and CFDs.

We set out to understand how far users of these apps might be showing these behaviours and getting these outcomes.

Our research

We undertook a survey with over 3,000 app users, sampling customers of 4 trading apps. We also included participants from a trading app of a more traditional investment platform, which does not have the features we were concerned about, as a comparator. We also undertook in-depth qualitative interviews with a sample of 20 app users.

We used a method from academic literature, using a hypothetical investment decision to categorise participants into high, medium or low risk aversion or not risk averse. We compared these preferences to their reported investment choices. For example, if they chose a high-risk investment (such as cryptoassets) but had a low or medium risk appetite, we classified them as engaging in investing that was potentially beyond their risk appetite.

Gambling behaviour in a population is often assessed using the Problem Gambling Severity Index (PGSI). It asks a range of questions around problematic behaviour such as ‘Have you bet more than you could really afford to lose?’ With academic advice, we adapted this in our survey for investing. We grouped respondents according to the degree of problematic behaviour they report. Scores of over 8 on the PGSI are classed as ‘problem gambling’, with those scoring between 3 and 7 classed as ‘at-risk’. Although our research looked at investments, we use the term ‘problem gambling behaviour’ here for consistency with previous studies.

We also asked a range of questions to understand wider investing behaviours and vulnerabilities such as how frequently they traded, their financial resilience and financial literacy.

Trading apps using more features of concern were associated with consumers investing potentially beyond their risk appetite, problem gambling behaviours and frequent trading

Consumer harms – investing potentially beyond their risk appetite

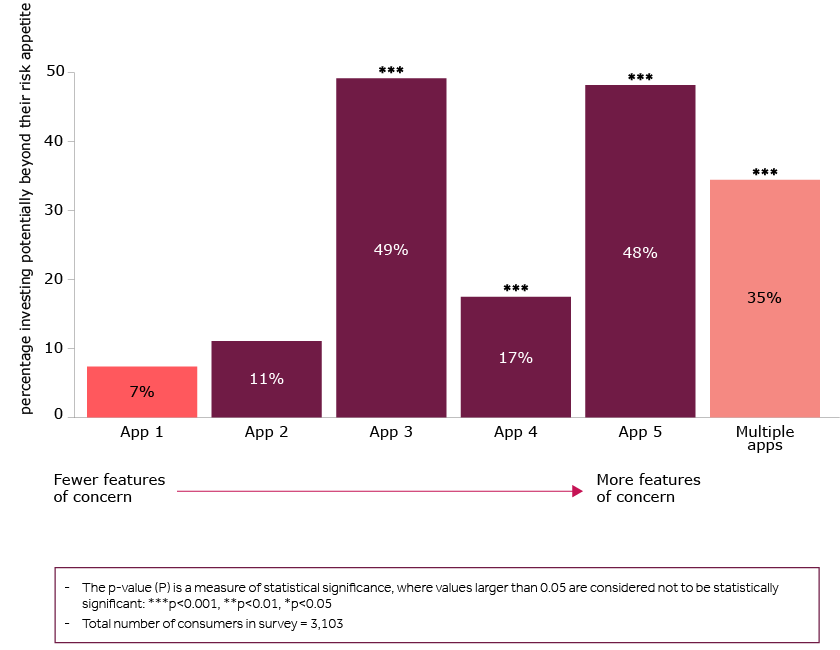

In Figures 5 and 6, moving from left to right takes you from the app with no features of concern (our comparator) through increasing counts of features, as identified in our evaluation. For 2 of the apps with features of concern, which also offer crypto assets, almost 50% of customers in our survey invested in products that were potentially beyond their risk appetite. For apps which did not offer cryptocurrency, this was much lower. However, it remained at a higher level than the comparator.

Figure 5: The proportion of customers engaging in investing potentially beyond their risk appetite

In our survey, being ‘at-risk’ of problem gambling behaviour is correlated with other commonly used indicators of vulnerability such as low financial resilience and low financial literacy. This indicates a subset of financially vulnerable customers are exhibiting problem gambling-like behaviour.

The association between gambling behaviours and investing on the trading app was one that participants in our qualitative research made without prompting. For example, one participant stated the various design features made the app feel ‘all very in your face and feels more like a sports betting app’. Another participant speaking about the frequent notifications stated they have an ‘addiction habit and I would literally be on the app all the time, so it is better I turn them off’.

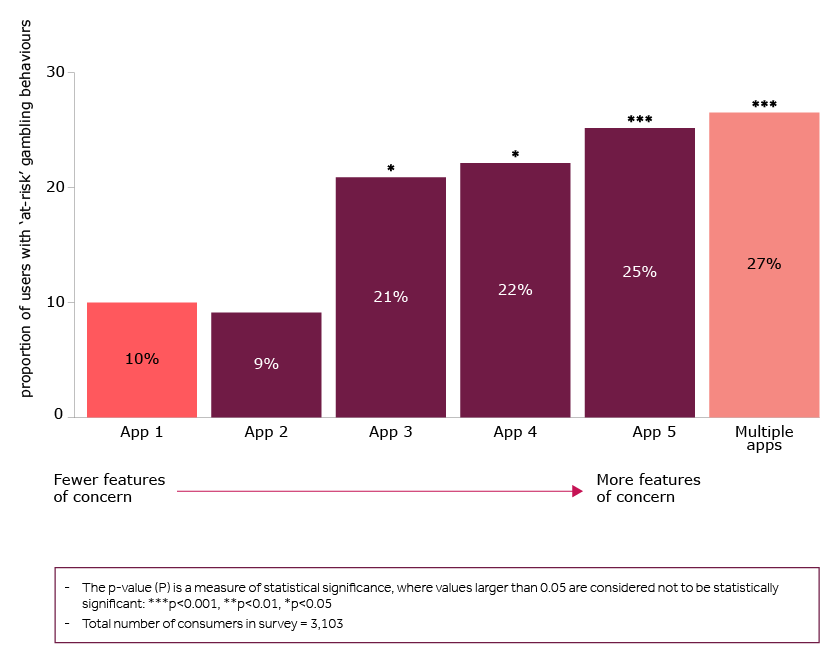

Consumer harms – problem gambling behaviour

Using the PGSI, 1 in 27 (3.75%) participants in our survey were classified as having ‘problem gambling behaviour’. This is a similar incidence to ‘problem gambling’ for online gamblers, at 1 in 29 (3.5%). If we widen the groups to include those who are ‘at-risk’ of problem gambling behaviour (scoring 3+ on the PGSI), it increases to around 1 in 5 (over 20%) trading app customers – with more at-risk behaviours being seen on the apps with more features of concern. This association holds even when controlling for demographic variables.

Figure 6: The proportion of users ‘at-risk’ of gambling (as measured by scoring 3+ on the PGSI) on each trading app

In our survey, being ‘at-risk’ of problem gambling behaviour is correlated with other commonly used indicators of vulnerability such as low financial resilience and low financial literacy. This indicates a subset of financially vulnerable customers are exhibiting problem gambling-like behaviour.

The association between gambling behaviours and investing on the trading app was one that participants in our qualitative research made without prompting. For example, one participant stated the various design features made the app feel 'all very in your face and feels more like a sports betting app'. Another participant speaking about the frequent notifications stated they have an 'addiction habit and I would literally be on the app all the time, so it is better I turn them off'.

Next steps

The potential 'problem-gambling' behaviours our research has uncovered are associated with apps that have more gamification and sludge design elements. It does not tell us whether the design features themselves are causing poor outcomes such as investing in products beyond one’s risk appetite. This would require further investigation. We may look at aspects of this through future research and explore potential wider context and financial vulnerabilities for users of these apps, such as whether they borrow and invest and the scale of any losses.

The FCA is taking steps to follow up with some of the firms whose trading apps we reviewed and has stated that 'some product design features could be contributing to problematic, even gambling-like, investor behaviour. We expect all firms that offer stock trading to consumers to review and, where appropriate, make improvements to their products based on these findings. They should also ensure they are providing support to their customers, particularly those in vulnerable circumstances or those showing signs of problem gambling behaviour. To ensure customers are being treated fairly and ahead of the new Consumer Duty coming into force next year, all firms should be reviewing their products now to ensure they are fit for purpose.'